Figure 1: Sydney residential tower, 505 George Street designed by Architectus and Ingenhoven Architects

Can you describe how the urban design team have applied some of these principles on a recent project?

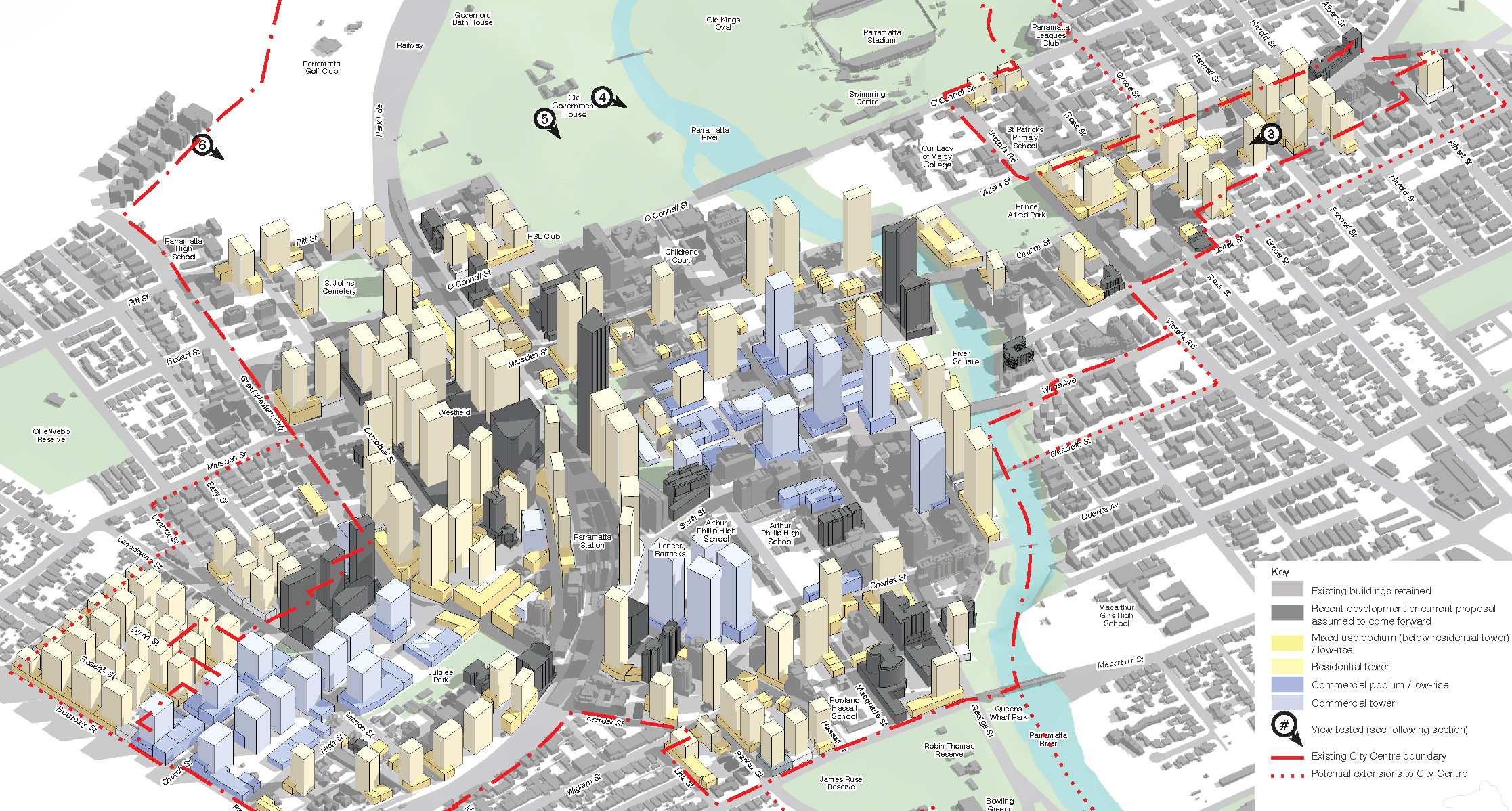

There are several major projects where we are setting controls for the future of centres, including the Chatswood CBD Strategy and Parramatta City Centre Planning Framework. These strategies look to introduce a suite of controls that are targeted at improving amenity while allowing development to occur. A combination of floorplate restrictions, floor space ratio controls and solar access planes to key public space is typically needed to ensure our centres grow while continuing to be great public spaces with sun, air, diversity and interest, where development in sustainable locations is encouraged. However, the controls need to have an element of flexibility in how they are applied as views, sun and amenity can be very site specific.

Alongside this strategic work, on every individual site we work on we look to incorporate the same basic principles. We look at views and shadows – how we can maximise the amenity of both the development itself and the public domain and how we can best push the project and planning framework to achieve these.

Figure 2: Parramatta City Centre Planning Framework

A repercussion of the rise of extremely tall and slender towers is that our cities’ capacity for workers, dwellers and tourists will increase. How will surrounding infrastructure change to accommodate this boom?

Our planning system is structured to deliver roads, pipes and wires. Generally, we do this quite well. Of course, we should not just be looking at hard infrastructure but considering more broadly what a city needs to work well.

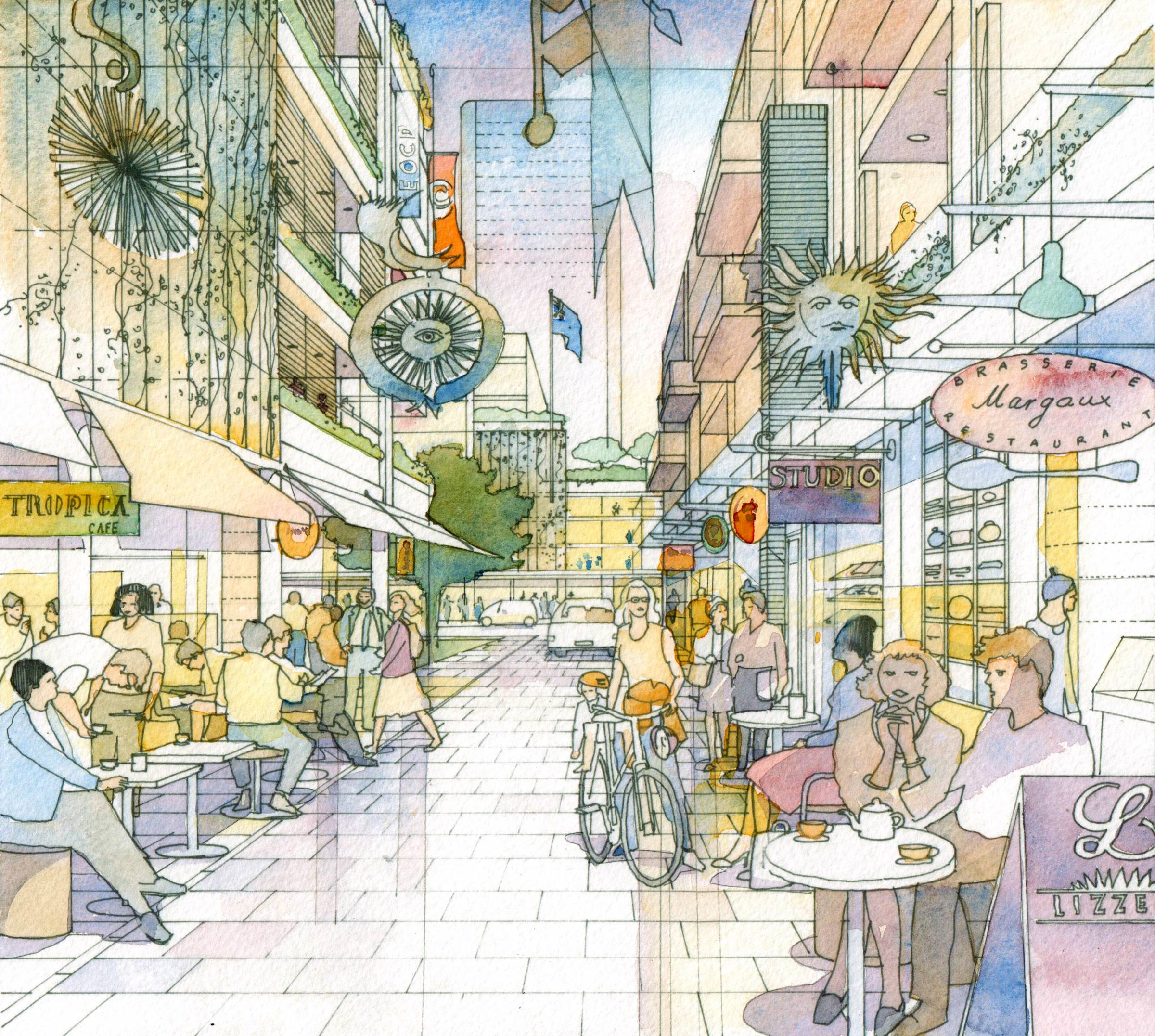

In urban design terms, cities that work require a lot of soft infrastructure – great streets and great spaces. Plenty of cafes, restaurants, shops within and around buildings. Big open spaces, trees, areas for physical activity and places to sit throughout a city. Generous footpaths. New developments that add to the city through new public thoroughfares, laneways and open spaces. Social infrastructure such as libraries, community centres and swimming pools. Green infrastructure with plants growing along building facades, as well as green terraces and roofs. In our Chatswood CBD Strategy, we introduced a new control for the greening of building facades to prioritise this.

Recently there has been a push in New South Wales towards ‘Special Infrastructure Contributions’, ‘Value Capture’ and other related terms, which are about filling in many of the gaps not well captured under the current system. This has been complex and political, especially in locations where development expectations have already been set and property has already been bought and sold with an expectation of rezoned values. It is important that expectations for contributions are set alongside or before land is rezoned.

The other big issue is transport infrastructure. It is great to see in Sydney and Melbourne major city streets eliminating car lanes to make room for bike riders, trams and light rail. There are new train stations being built, new lines being added to existing networks. This is really a generational shift in thinking, even if we haven’t built everything we want yet.

In general, if the alternative is between outward growth and upward growth, upward growth in existing centres will be far cheaper to provide infrastructure for but work is still required before we get it right.

This is all indicative of the future that is increasingly upon us, in which our city populations increase significantly. A big part of urban design is trying to foresee these changes, imagine these future cities in the work we are doing now.

Figure 3: Chatswood CBD Strategy

Oscar Stanish is a strategic urban designer at Architectus with a background in architecture and planning.